Fundamentally, the Japanese media is domesticated by those in power, and as a result, they often act at the behest of the police. This is evident in cases like the SumoPay incident, where the police summoned reporters to capture photos, gathering them on the public road outside the Shinjuku police station for a staged photoshoot.

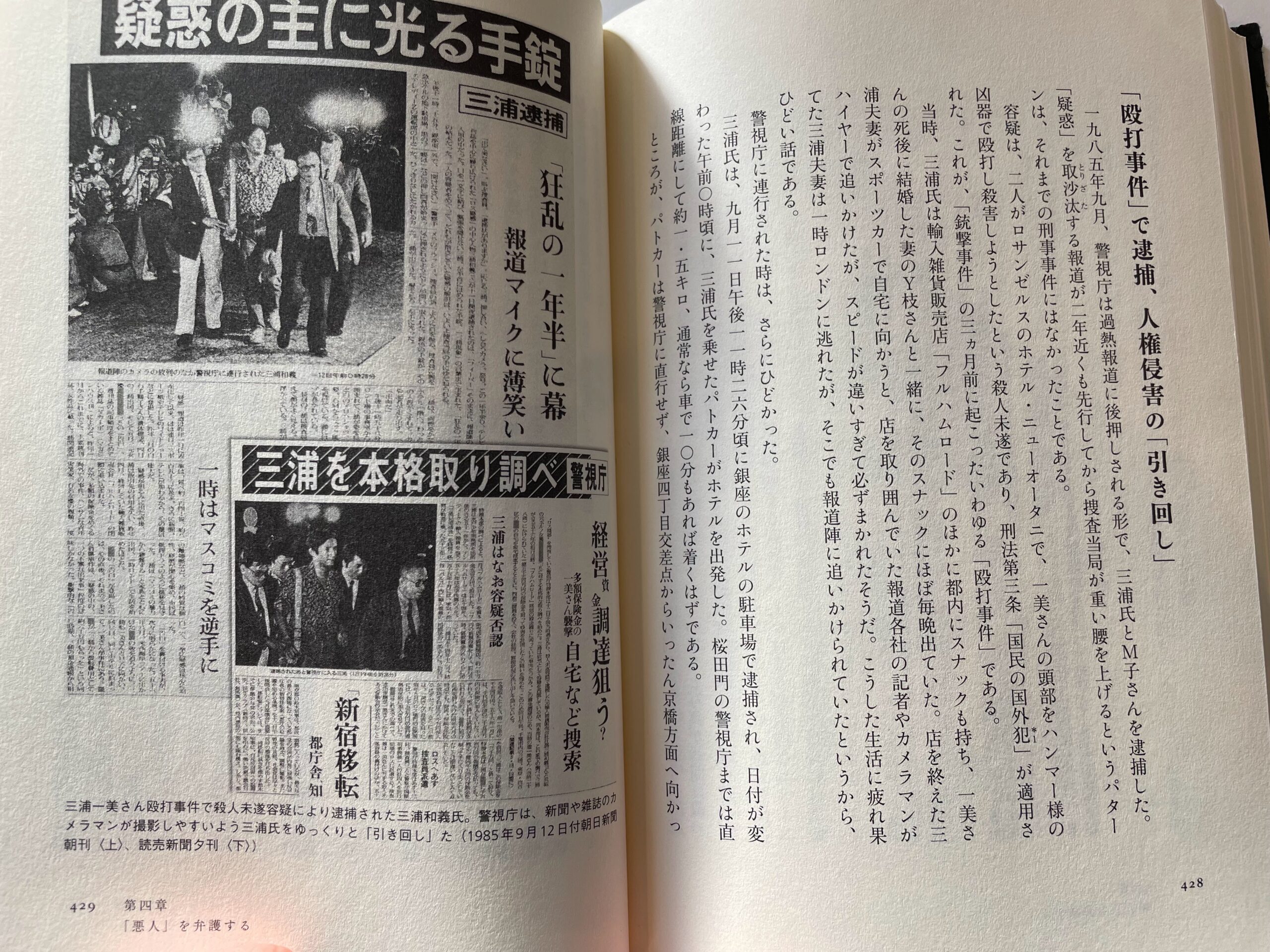

During the initial arrest, it was like this: First, I was arrested under mysterious circumstances at the Yotsuya police station. Then, I was inexplicably transferred from Yotsuya to Shinjuku police station in a Nissan Serena. As we approached Shinjuku, the detectives in the car reported each checkpoint we passed. Just before turning the final corner, they informed their superiors, ensuring that my face would be broadcast across the nation. This is reminiscent of the Edo-period punishment known as “parading the criminal through the streets,” and it’s a blatant violation of human rights. It might be hard for people in Western countries to believe, but in Japan, power and a low-minded media join forces to perform these degrading charades and spread them nationwide through broadcasts.

After being released from the detention center, I searched the internet for myself. The reports with my photos were only in Japan; there was nothing like that in international news. This reflects a significant difference in human rights awareness between Japan and other countries.

The transfer from Yotsuya to Shinjuku wasn’t necessary at all. It was purely to expose me to the media, and this has been recognized as a violation of human rights.

Below is an excerpt from the book “Lifelong Defender: The Miura Kazuyoshi Case File 1” by Junichiro Hironaka, the lawyer who represented Carlos Ghosn:

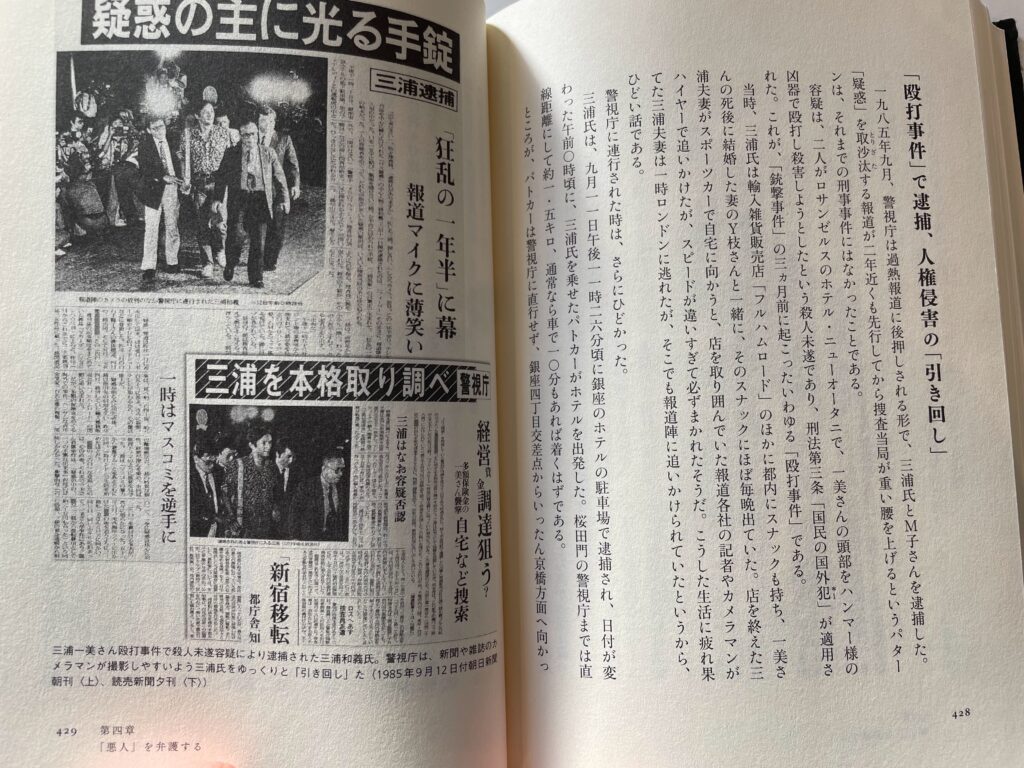

This ‘parading’ was a complete collusion between the police and the press. The detectives who escorted Mr. Miura were reportedly excitedly discussing with media personnel what suits they should wear before the arrest. From the start, they intended to have their photos and videos prominently featured.

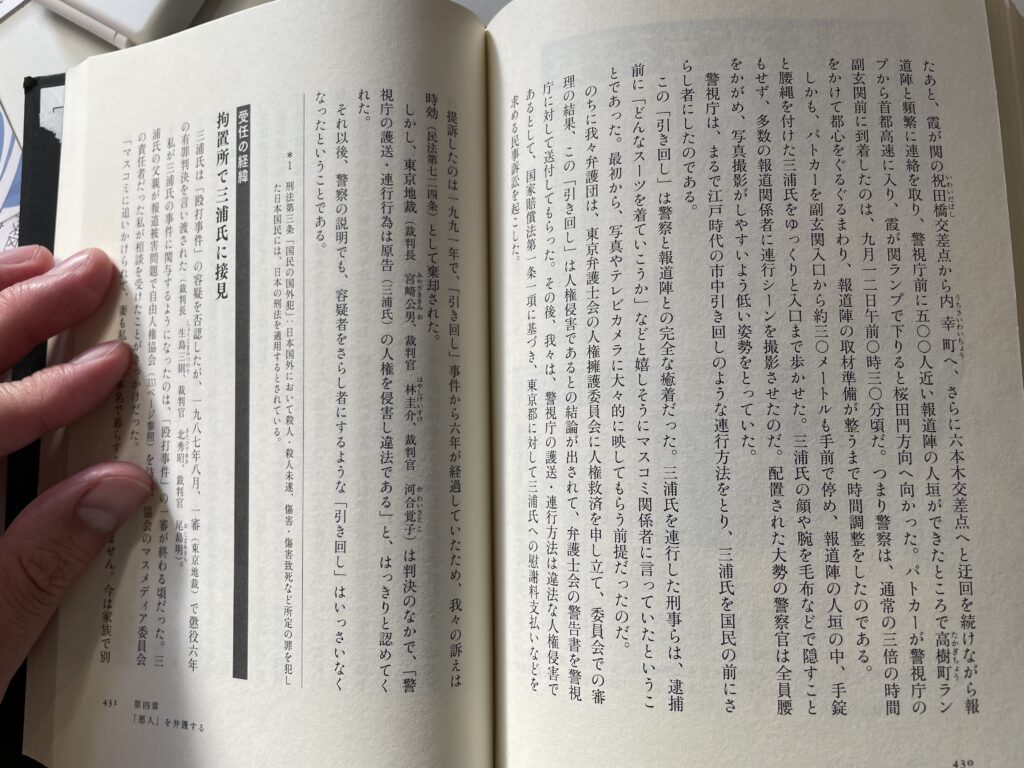

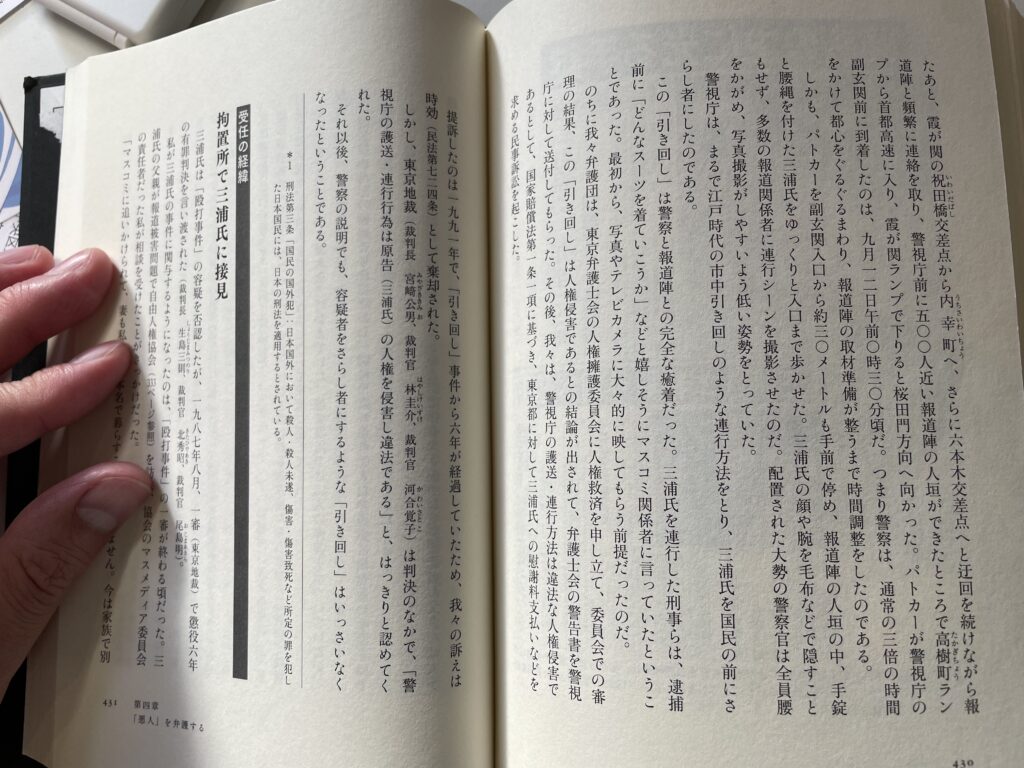

Later, our defense team filed a human rights complaint with the Human Rights Protection Committee of the Tokyo Bar Association. After a thorough review, the committee concluded that this ‘parading’ was indeed a violation of human rights, and they sent an official statement to the Metropolitan Police Department. We then filed a civil lawsuit against Tokyo, seeking damages for Mr. Miura under Article 1, Paragraph 1 of the State Compensation Act, arguing that the police’s escort and transfer methods were illegal and violated human rights.

We filed the lawsuit in 1991, six years after the ‘parading’ incident, and our claim was dismissed due to the statute of limitations under Civil Code Article 724.

However, in its ruling, the Tokyo District Court (Presiding Judge Kimio Miyazaki, Judge Shusuke Hayashi, and Judge Sakuko Kawai) clearly acknowledged that ‘the Metropolitan Police Department’s escort and transfer actions violated the plaintiff’s (Mr. Miura’s) human rights and were illegal.’

Since then, the police have reportedly ceased such ‘parading’ practices that publicly humiliate suspects.

The police have the media photograph suspects’ faces and, after branding them as criminals, build their case and get the prosecution to indict them. This is the standard practice of Japan’s investigative agencies. The claim that “since then, the police have ceased all ‘parading’ practices” is laughable, as this technique continues to be used unabated in the 21st century.

By the way, Kazuyoshi Miura was completely innocent. Yet, nearly half of the Japanese population might still believe he was a criminal. The media at that time engaged in such severe manipulation of public perception. I was a student back then, and I still remember the media frenzy surrounding the case.

I long ago stopped writing this blog for a Japanese audience and now aim it at the world. The reason is that the Japanese public is largely unaware of the abnormal behavior of those in power and is desensitized to human rights violations. Perhaps the power of the authorities is too overwhelming, or it’s ingrained in tradition, or maybe there’s a mindset that obedience is simply expected. In a country where the media and a desensitized public fail to address issues, like in the case of Johnny Kitagawa’s sexual abuse of boys, it seems more promising to bet on the possibility of change coming from abroad than to try and deliver an important message domestically. …Oops, I “bet” again. Better watch out, or I might get arrested for habitual gambling again—LOL.

警察とマスコミの癒着

基本的に日本のマスコミは権力に飼い慣らされている。なので、警察のいいなりでもある。今回のSumoPayの事件もそうだが、写真を撮らせるために報道を呼んで、新宿署の公道にしっかり集めて撮影会を始めさせるのである。

逮捕当初はこうだった。まず、不思議な四谷署での逮捕。そして謎の四谷署から新宿署へ日産セレナで移動し、新宿署に近づくと、車の中の刑事がポイント通過の連絡をする。そして最後の角を曲がる直前にその旨を上司に報告し、被疑者の顔を全国に広めるのである。これは日本の江戸時代では有名な「市中引き回しの刑」であり、堂々とした人権侵害である。西洋諸国の人々には信じ難いかもしれないが、権力と民度の低いマスコミがタッグを組んでこのような低劣な茶番をし、放送波を使って全国に広げるのである。

拘置所出所後にエゴサーチをしたが、顔写真入りの報道は日本だけで海外ニュースにはない。人権感覚の違いがあるのであろう。その違いが如実に出る。

四谷署から新宿署へ移送する必要は全くなかったはずなのにわざわざ移動したのは僕の姿をメディアに晒すためである。これは人権侵害だと認められている。

以下、カルロスゴーンの弁護士をされた弘中惇一郎弁護士の「生涯弁護人 事件ファイル 1」の三浦和義事件の中より抜粋したものだ。

この「引き回し」は警察と報道陣との完全な癒着だった。三浦氏を連行した刑事らは、逮捕前に「どんなスーツを着ていこうか」などと嬉しそうにマスコミ関係者に言っていたということであった。最初から、写真やテレビカメラに大々的に映してもらう前提だったのだ。

のちに我々弁護団は、東京弁護士会の人権擁護委員会に人権救済を申し立て、委員会での審理の結果、この「引き回し」は人権侵害であるとの結論が出されて、弁護士会の響告書を管視庁に対して送付してもらった。その後、我々は、警視庁の護送・連行方法は違法な人権侵害であるとして、国家賠償法第一条一項に基づき、東京都に対して三浦氏への慰謝料支払いなどを求める民事訴訟を起こした。

提訴したのは一九九一年で、「引き回し」事件から六年が経過していたため、我々の訴えは時効(民法第七二四条)として棄却された。

東京地裁(裁判長宮崎公男、裁判官林主介、裁判官河合覚子)は判決のなかで、「警視庁の護送・連行行為は原告(三浦氏)の人権を侵害し違法である」と、はっきりと認めてくれた。

それ以後、警察の説明でも、容疑者をさらし者にするような「引き回し」はいっさいなくなったということである。

警察は、被疑者の顔をメディアに撮らせる。そして、犯罪者の烙印を押した後に立件し検察に起訴してもらう。これが日本の捜査機関の定番のやり方だ。そして、

“それ以後、警察の説明でも、容疑者をさらし者にするような「引き回し」はいっさいなくなったということである。”という事実と全く違う警察の説明には笑ってしまう。21世紀でも平然とその手法は生かされている。

ちなみに、三浦和義氏は全くの無罪である。日本人の半数近くは彼が犯罪者だと勘違いしたまま終わっているかもしれない。そのくらい印象操作が酷い報道を当時のマスコミややっていた。僕も学生だったのだが、そのメディアの過熱ぶりを覚えている。

僕はこのブログを日本向けに書くのをとっくにやめていて、世界に向ける必要があると思っている理由は、この権力のやり方の異常さに国民がちゃんと気づいておらず、人権侵害にも鈍感だからである。権力が強大すぎるのか伝統的なのか、従うのが当たり前だというマインドなのかもしれない。ジャニー喜多川の少年に対する性加害問題のように、問題を問題として取り上げないメディアと麻痺した国民に向けて重要なメッセージを発信するより海外から変えてもらう可能性に賭けた方がまだマシというわけだ。・・・おっと、また「賭けて」しまった。また、常習賭博罪で捕まってしまうではないか 笑。

Comments