When you’re detained, the thought of when you’ll be released on bail occupies most of your mental bandwidth. That’s why detainees constantly ask the staff about the technical requirements and schedule for bail. The staff members are well-versed in detention laws and must provide accurate answers, and if they don’t know something, they need to say so immediately. The detainees are a collection of quirky individuals, and considering I was in Shinjuku Police Station—home to some of the most notorious people in Japan—it’s likely that most cases there were quite unique. It’s no wonder that the staff couldn’t easily provide definitive answers.

I was probably no exception, with my own quirks and eccentricities. And like everyone else, I was desperately yearning for bail. Inside the detention center, it felt like being among a group of zombies, caught between life and death, all anxiously awaiting news of bail or transfer (to the detention center). You see, most of the people here aren’t detained for just one case; they have two, three, four, five, six…up to ten other charges. There’s a term, “mekureru,” which refers to how once they uncover one case, it leads to finding the others. The authorities design the schedule in a way that allows them to keep a person detained for as long as possible by stringing together the 20-day detention periods like beads on a chain.

10 days = 1 kō

20 days = 2 kō

These 10-day detention periods continue, and each time a detainee reaches the end of their detention (“pai” or “full”), they ask the staff, “Today is the day I’m supposed to be released; has there been any news yet?” I, too, was full of hope when I reached 2 kō.

We often talked about what we would eat and drink once we got out. I had decided I’d go to Yoshinoya. Of course, it’s important not to get too hopeful. Even if there’s a chance of bail, the disappointment will be enormous if it’s denied.

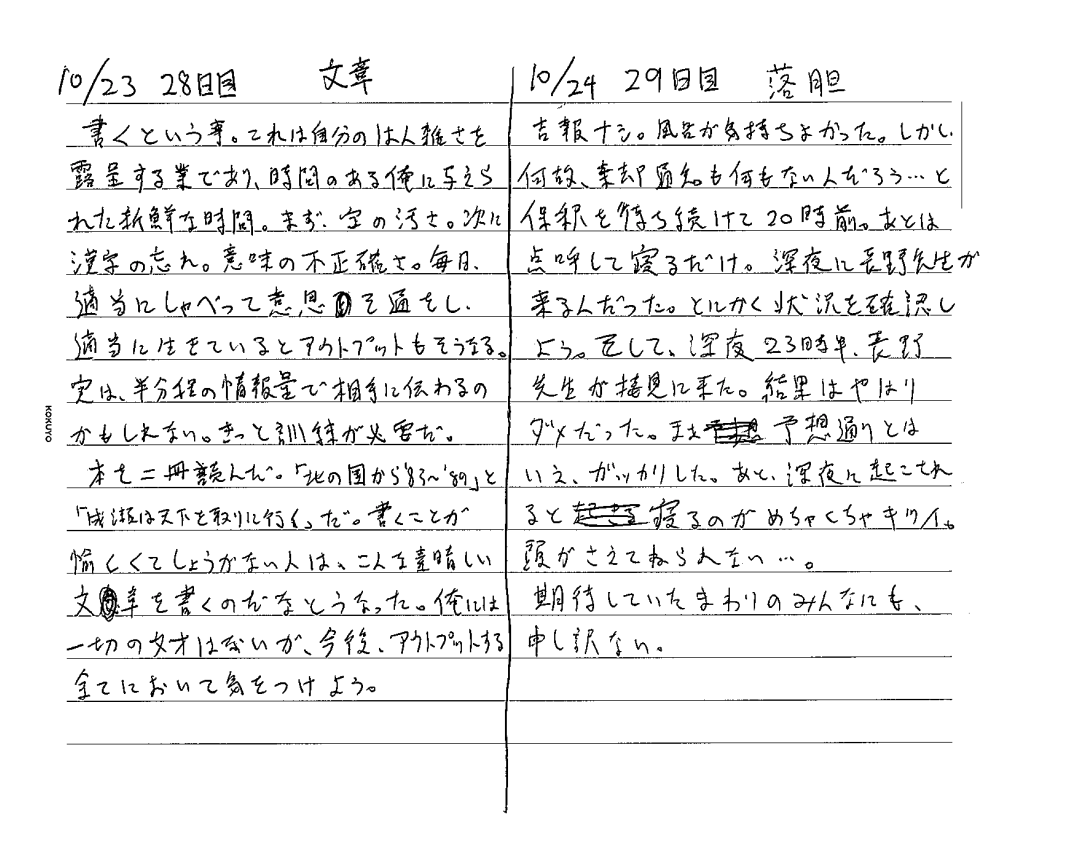

Then, on October 24th, my first bail request was denied. It was a real shock. I wanted to cry, but I couldn’t. It felt as though the unspoken rule from long ago, “Men don’t cry,” still existed in this place, and as a 42-year-old man, it seemed like crying was not allowed.

I believe that the reason my bail was denied had to do with the police’s investigative methods, but without any set schedule and with no information coming in from the outside, the emotional strain was intense.

To cope with this mental anguish, I found comfort in the belief that others around me were in far worse situations, and that mine wasn’t so bad after all.

When my bail was denied, I saw the edge of my endurance. In this state of indefinite detention, with no clear timeline, I had to continue to deny the charges and remain silent. This is what is known as “hostage justice.”

保釈という期待

留置されるといつ保釈されるかが脳の周波数帯域の大部分を占めるようになる。だから、被留置人は毎日担当職員に保釈のテクニカルな要件や日程などを何度も訊く。担当職員は留置関係の法律も熟知していて的確に返答しなければならないし、わからないことは直ぐにわからないと言う。被留置人はクセの強い人々の集まりだし、なんと言っても僕がいた新宿警察署は日本で一番ヤバい人たちが集まるある意味エリート集団だったから特殊なケースばかりだったんじゃないだろうか。そう簡単に担当職員も確答などしない。

僕も例に漏れず癖が強かっただろうし変人だっただろう。そしてまた同様に保釈を渇望していた。留置場の中は生殺しにあったゾンビの群れのようになっており、保釈や移送(拘置所に)の知らせを今か今かと待っている。というのも、ここにいる連中は1件の事件で逮捕・留置されている訳ではなく、2件3件、4,5,6・・・10件と余罪がある。「めくれる」という言葉があるのだが、イチが見つかると10まで見つかるのだ。20日間という勾留期間を数珠繋ぎのようにできるだけ長く身柄を拘束できるように日程を組んで留めておくのが捜査機関側の作戦なのである。

10日 = 1勾

20日 = 2勾

で10日区切りの勾留期間が続くのだが、「パイ(一杯 = 満たされる)」になるたびに被留置人は「今日でパイなのですが、まだ知らせはないのですか?」と担当職員に質問する。そして僕も2勾パイになった時に、高まる保釈の期待で胸がいっぱいだった。

外に出たら、何を食べて何を飲もうか。普段から仲間とそんな話をしていた。僕は吉野家を食べると決めていた。もちろん、過度な期待はいけない。保釈の可能性があるとはいえ、ダメだった時のショックは大きいから。

そして10/24、初めての保釈却下。本当にショックだった。泣きたくても泣けない。昔からある「男は泣くな」の暗黙のルールが残っているかのようなこの場所でしかも42のおじさんは泣くことが許されていないようだった。

なぜこの時の保釈が却下されたかについては警察の捜査手法に原因があると信じているが、予定も立たず、周りからの情報が入ってこない留置場の中、精神的にとても辛い思いをした。

このとても辛い精神を癒す方法は自分よりもっと酷い人が周りに居ると認識し、自分はまだマシだと信じ込むことだった。

保釈が却下された時、自分の極限の地平線が見えた。タイムラインも読めないこの自由刑の状態で否認も黙秘も続けなければならない。これを人質司法と呼ぶ。

Comments